Understanding Powdery Mildew in Nurseries and Floriculture

What is Powdery Mildew?

If you’ve ever seen a white, dusty coating on your ornamentals or nursery plants, chances are you’ve met powdery mildew, a common and frustrating disease affecting a wide range of nursery and floriculture crops.

Powdery mildew is caused by a group of fungi that are host-specific, meaning the one on your roses won’t necessarily infect your zinnias or begonias. Still, many ornamental crops are vulnerable, including roses, hydrangeas, snapdragons, phlox, chrysanthemums, begonias, kalanchoes, and many woody shrubs like crape myrtle, lilac, and dogwood.

The good news? Powdery mildew is manageable, especially when addressed early and with integrated approaches.

Recognizing the Symptoms

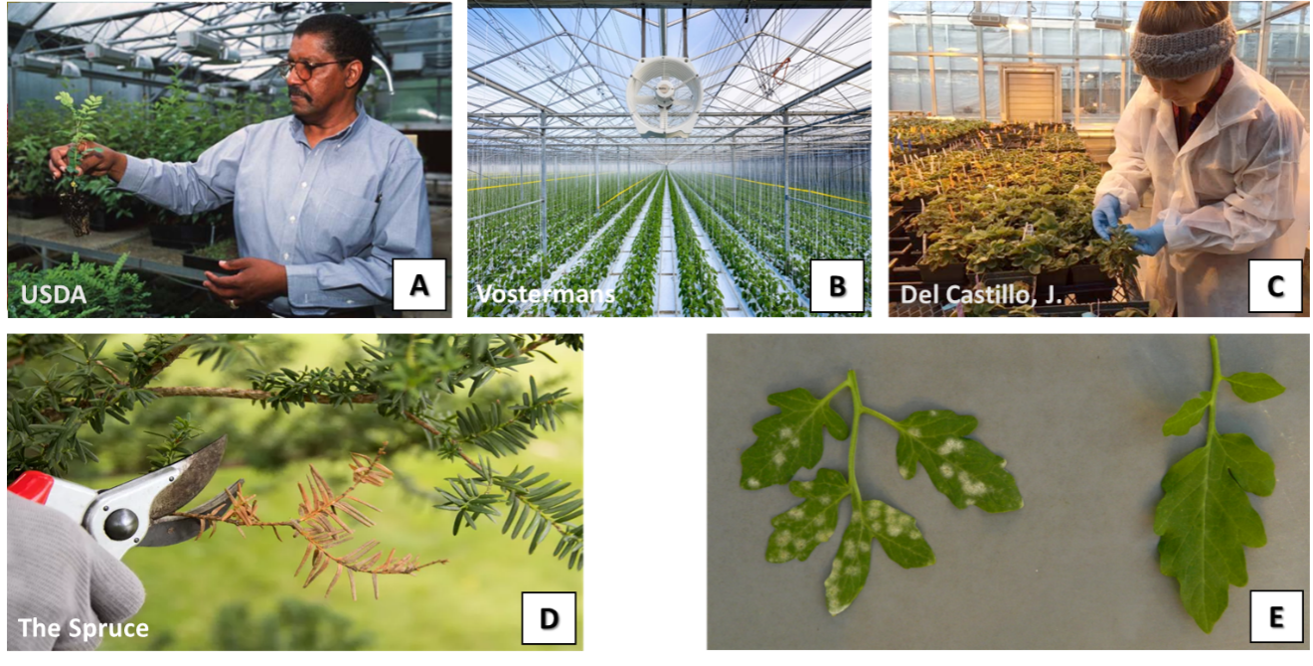

Powdery mildew typically starts as small, white, powder-like spots on leaf surfaces, especially on young, tender tissue (Fig. 1A). The white coating spreads and thickens over time, sometimes affecting stems, buds, or flowers (Fig. 1B-C). Other symptoms may include yellowing or browning of leaves, curling or distortion of new growth, stunted plants or premature leaf drop, reduced flower and stem quality.

Why Powdery Mildew Loves Nurseries & Greenhouses

Powdery mildew fungi are unusual in that they don’t need water to infect your plants. Instead, they thrive in environments with warm days and cool nights, high humidity (over 90%), shaded and low-light areas, overcrowded plant spacing, and mild temperatures (60–80°F). This makes greenhouse environments especially favorable. And because the fungi live on living tissue, they are excellent at hiding and surviving in buds, leaves, or plant debris.

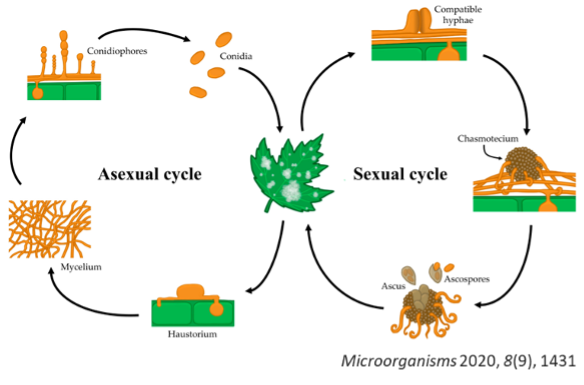

Lifecycle

Powdery mildew spreads primarily through airborne spores, which can germinate and infect new leaves within 6 hours under ideal conditions. The fungi feed from the surface, inserting tiny feeding structures (haustoria) into plant cells to draw nutrients (Fig. 2).

They survive between crops as spores in plant debris or as living mycelium on infected plants, including incoming nursery stock. With multiple cycles possible in a single growing season, catching the first signs is essential.

Best steps for a powdery mildew-free facility

- Start with Clean Plants: Inspect incoming stock carefully and avoid introducing diseased plants to your production areas.

- Improve Airflow & Reduce Humidity: Space plants adequately to improve light and reduce humidity between leaves. Use fans to circulate air evenly throughout greenhouses and vent greenhouses at night to drop humidity below 85–90%.

- Monitor Regularly: Scout at least weekly, check leaves in the middle of plants, especially those in shaded areas. If mildew is spotted, intensify scouting and isolate affected groups when possible.

- Prune and Sanitize: Remove and destroy infected leaves or stems (seal in plastic before disposal) and eliminate volunteer plants or weeds under benches or around greenhouses. Disinfect tools between areas where the disease is active.

- Resistant Cultivars: While resistant varieties are more available for some crops (like crape myrtle, dogwood, or certain rose types), nursery and floriculture growers should ask suppliers about disease resistance, especially for historically susceptible crops.

- Temperature: Powdery mildew tends to be favored by mild temperatures and may slow down when conditions become hotter. In some cases, short periods of higher temperatures (above 90°F at the leaf surface) may help reduce disease pressure. However, be cautious, many ornamental crops are sensitive to heat, so this is not always a practical approach!!

Biological & Low-Impact Solutions

Some growers have explored alternative options to supplement cultural controls, such as potassium bicarbonate products, horticultural oils, sulfur, Reynoutria sachalinensis extracts, bacillus-based biologicals, and red or UV light exposure during the dark period (experimental but promising for greenhouse crops). But remember, coverage is key; these products are most effective when they thoroughly contact mildew colonies, including leaf undersides.

Avoiding Fungicide Resistance (If You Use Them)

Powdery mildew is highly prone to resistance, so if you do resort to fungicides, please rotate products with different modes of action. Best results have been found using FRAC codes 3, 3+7, 7+11, 11, 9+12, and M5 (check the FRAC group on the label) and do not rely on one product repeatedly across the crop cycle. Always follow re-entry intervals and label rates carefully.

From Recent Research

A recent study by Jennings et al., (2024) looked at how well different rates and spray intervals of Postiva® (pydiflumetofen + difenoconazole) controlled powdery mildew on bigleaf hydrangeas grown in both greenhouse and shade house conditions. The disease developed naturally, and the fungicide was applied every 2, 4, or 6 weeks at low (1.1 mL/L), medium (1.6 mL/L), and high rates (2.2 mL/L). A commonly used fungicide (Mural® at 0.5 g/L) was also included for comparison, along with untreated plants as a control. Results showed that all fungicide treatments significantly reduced disease and leaf drop compared to untreated plants. Interestingly, the low rate of Postiva® applied every 6 weeks was just as effective as higher rates and more frequent sprays. Then, the study suggests that using the lowest labeled rate of Postiva® on a 6-week schedule is a practical and cost-effective option for managing powdery mildew in nursery-grown hydrangeas.

Another recent study by Faysal-Gurel and Bika (2021) evaluated 12 treatments, including sanitizers, biorational products, and fungicides, for managing powdery mildew on ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius). All treatments significantly reduced disease severity compared to the untreated control. The most effective products included:

- Azoxystrobin + benzovindiflupyr (Mural® at 0.37 and 0.52 g/L, applied at 7- and 14-day intervals, respectively)

- Chlorothalonil + propiconazole (Concert II® at 2.34 and 2.73 mL/L, applied at 7- and 14-day intervals, respectively)

- Azoxystrobin + tebuconazole (FRAC 11 + 3, at 0.37 and 0.56 g/L, applied every 14 days)

- Giant knotweed extract (Reynoutria sachalinensis) (Regalia® at 10 mL/L or 1%, applied every 7 days)

None of the treatments negatively impacted plant growth (height or width). However, mild phytotoxicity was observed under high temperatures in some treatments, particularly with hydrogen peroxide + peroxyacetic acid (ZeroTol 2.0 at 10 and 20 mL/L or 1 and 2% applied every 7 days).

References

Jennings, C., Simmons, T., Parajuli, M., Oksel, C., Liyanapathiranage, P., Hikkaduwa Epa Liyanage, K., & Baysal-Gurel, F. (2024). Chemical Control of Powdery Mildew of Bigleaf Hydrangea. HortScience, 59(2), 173-178. https://www.doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI17500-23

Baysal-Gurel, F. & Bika, R. (2021). Management of Powdery Mildew on Ninebark Using Sanitizers, Biorational Products, and Fungicides. HortScience, 56(5), 532-537. https://www.doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI15691-21